When we look at how a project is doing, we compare it against our intentions and our plans.

We ask ourselves questions like, "I've noticed that over the last several weeks we've been way off schedule. What might make this project run better? "

Then we say, "Oh, I know, we can move some human resources from this part of the project to this other part of the project and we'll finish on time."

We do this and we notice that, rather quickly, we are back on schedule. We track this for weeks.

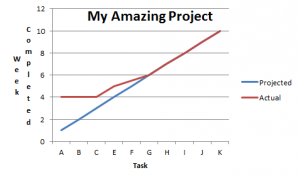

Our graph might look like this....

After our change, our actual work completion fell right in line!

Then we say, "I made a great decision and achieved my goals."

Good for me.

Well, this is easy math, right? I wanted something, I did it. And my result occurred. I should get a bonus, a promotion, and perhaps a corner office.

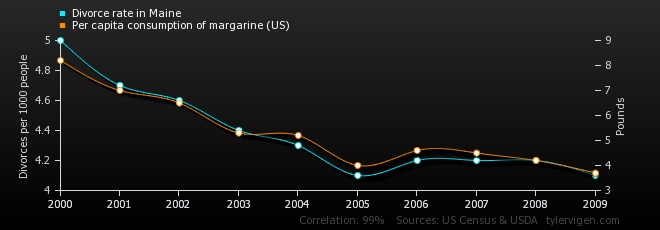

This is a correlation. We notice that something happens that happens right when something else does. We then assume that because one change happened and an effect perfectly matched it, that they are related. This type of deep thought also proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that divorces in Maine are directly caused by how much margarine we eat. Less margarine, it turns out, means less divorces. If only we would have known sooner!

Or we could be confusing correlation with causality.

Because we are people, managers often suffer from confusing correlation with causality. Pedants like to wave this in people's faces when an error in judgement occurs, but the fact is - we do this all the time in real life and its nearly impossible to avoid.

Confusion of correlation and causality has some deep seeded roots in our minds. Psychologists call this Illusory Correlation, a tendency in all people to draw conclusions from limited data sets. But simply knowing this isolated cognitive bias doesn't give us anything to act on. Looking at other biases give us a systems-view of what might be happening in the office and, therefore, some ways to avoid it.

Our confusion might stem from any number of well-studied cognitive biases:

Confirmation Bias - a common tendency for people to search out conclusions and data that confirms their original hypothesis. In this case, I made a change I thought would have a certain result and when that happened, I felt my hypothesis was confirmed. The problem is, there could have been any other number of factors that had an impact on that improvement. Early work could have been hampered by waiting for materials, decisions, or even just clarity. Later work could have been spurred-on by additional headcount. Or, worst of all (and rather common), early work could have been being done carefully and methodically and the time where the team was adhering to the schedule could have been done quickly and sloppily.

Availability Cascade - The more people around you repeat something or the more you repeat it, the more it seems true. So it seems like Steve Jobs single handedly built Apple, but maybe he had some help - otherwise he and Woz could have just stuck it out in the garage. In this case, the more I give presentations about how the shift I made in personnel made this project work, the more it will be accepted as true without any proof whatsoever.

Illusion of Control - We have an innate need to control the world around us. In order to give us a feeling of stability, we generate illusions of control in circumstances where we actually have very little control. In this case, I moved some people around and some change happened. I will then attribute that change to my actions. Now, here's the tricky bit - I now attribute the benefits to the change and am now likely to do it again in a future project. I am now creating a methodology based on my observations. But the improvement might not have been my change at all, it may have been the added attention I was paying to the project. It may have simply been greater managerial and team awareness of what needed to be done. What's sad here is that my illusion of control is based on the bad correlation - and that I really did have an impact, it just wasn't what I thought it was.

Placebo Effect - Following illusion of control, the team may have improved simply because they thought they were getting something that would help them improve. When the team bought into the improvement scheme, they also bought into improving at all. This invokes a Framing Effect where the change being brought frames the decisions and actions of the team. When people buy into a system to move them in a certain direction, the will naturally move in that direction. Why? Because they have direction! Quite often work groups in the office don't have adequate direction or vision to complete their work. Often, that was what they really lacked - it just happened to be delivered in a box labeled "organizational change" this time.

There are many more of these, but this is already becoming a long blog post. So let's talk about how we might mitigate them.

Mitigation

Just to say this again, being aware of a cognitive bias does not make us immune to the cognitive bias.

To mitigate these impacts, we need to understand one key thing about business decision making - we're never going to have all the information we need. Our goal is not to eliminate the impacts of cognitive bias on our decision making. The goal is to be wary of our own decisions and to be vigilant in asking hard questions.

Do I have enough information?

Is that really the root cause of that effect I am observing?

What is the real risk in what I'm about to undertake?

Everyone is saying our new plan will work, why won't it?

In short, taking a step back and considering the true root causes of problems, the true impacts of potential solutions, and the role that human variables will play in delivery are the key mitigation to cognitive bias issues in our work.

Want more? This is discussed in more detail in our book, Why Plans Fail.