"How do we prioritize all this work?" "What are mechanisms you use to prioritize?" "What if I have a lot of options that are all equal?" These are all valid questions and prioritization is an important function of both home and professional work. However, we find most often that prioritization issues, like trust issues, are a symptom of deeper problems. This video discusses what some of those root causes are and how we at Modus Cooperandi approach them.

The Lean Brain, Post 5: Improvement is Not an Option

Lean says: Seek Perfection What your brain says: This is the way we’ve always done things around here. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. It’s not “my job” to improve.

What’s at play here: Status quo bias. Zero-risk bias. Resistance to Change. Learned helplessness.

While Lean’s focus on respect for people endows the worker with the ability to implement change for improvement’s sake as they see fit, that sense of agency must be coupled with the psychological safety that allows them the freedom to fail.

Only in a safe-to-fail environment - one where employees are comfortable being vulnerable seeking out and attempting to solve sticky problems - can we tap into workers’ deepest potential and produce a culture of learners, experimenters, and creative problem-solvers, hallmarks of a successful Lean culture, one that recognizes overlooking human potential is among the greatest wastes.

One way to accomplish this is to ensure that the risk of failure is kept to a minimum.

Why?

Our brains are wired to do two things exceptionally well: to minimize risk, and maximize reward. Motivated to affect these ends in the service of our survival, our brains place a premium on certainty. Not only is exploring something novel energy-intensive (creating new neural pathways requires work), any deviation from the status quo - even if it is in own own best interest - is perceived as a risk to be avoided. Cutting-edge approaches, untested actions that run counter to the familiar present themselves as a threat to our brains much in the way the rustle of a potential predator lurking in the tall grass did for prehistoric man.

Despite its neuroplasticity, our brains are predisposed to resist the ambiguity inherent to change and the resultant stress science shows, triggers actual physiological discomfort.

So despite recognition that current conditions could benefit from improvement, it is understandable that we instinctively frame conversations about change in terms of its (perceived) risk rather than its potential (perceived) reward.

To be sure, there’s an obvious irony at play here: man’s survival as a species was and remains indebted to its ability to adapt to its ever-changing environment. While our brains might intensely dislike and do everything it can to resist change, neuroplasticity nevertheless allows it to create new neural pathways and by extension, new habits.

Which is fortunate. Because for both the individual and the organization in which s/he works, maintaining the status quo is a risk.

How to mitigate:

Evolutionary trumps revolutionary. Research reveals that large changes engage the amygdala - the part of our limbic system that processes emotions and responds to threats.

When it comes to taking steps towards improvement, the brain likes its change in comfortable doses.

Small scale, incremental improvements are powerful because the proposed change bypasses the amygdala – the brain’s fight or flight mechanism – so there is less resistance, less fear of the unknown and by extension, less fear of failure.

Not only are gradual changes physiologically more comfortable to engage in, they likewise have a lower cost of failure, and are easier to sustain and build upon.

Earlier posts in this series:

Introduction: 5 Ways Our Brain Can Thwart Lean

Post 1: Value is a Conversation

Post 2: Visualization Begets Alignment

Post 3: Flow: You Can’t Step in the Same River Twice

Post 4: Push is Blind. Pull is Informed. See Beyond the Silo.

Tonianne is partner & principal consultant at Modus Cooperandi, co-author of the Shingo Research and Publication Award winning Personal Kanban: Mapping Work | Navigating Life, co-founder of Kaizen Camp™ and Modus Institute. Toni explores the relationship between performance, motivation, and neuroscience, is passionate about the roles intention, collaboration, value-creation, and happiness play in “the future of work,” and appreciative of the ways in which psychology, Lean, systems thinking, and the work of W. Edwards Deming can facilitate these ends. She enjoys Coltrane, shoots Nikon, butchers the Italian language (much to the embarrassment of her family), is a single malt enthusiast, and is head over heels in love with her adopted home, Seattle. Follow her on Twitter @Sprezzatura.

The Lean Brain, Post 3: Flow - You Can't Step in the Same River Twice

Lean says: Manage Flow Your brain says: My work isn’t linear. My day is filled with interruptions and so I don’t have the “luxury” of flow.

What’s at play here: Functional Fixedness.

If there is one area where there’s not an obvious transfer of Lean principles from manufacturing to knowledge work, it’s understanding how flow can in fact be achieved when work is creative and contextual rather than isolated and prefigured.

On the factory floor, workers create a fairly static set of tangible products in a predictable way, while constantly aiming to reduce variation to produce uniform output.

In the office, whether their work products are largely inventive (e.g. software development) or relatively standardized (responding to a customer service call, for instance), knowledge work is fraught with variation.

Myriad people, products, projects, processes, experience levels, and information sources (both tacit and explicit), coupled with the requests for clarity and / or adjustment these constituencies make can combine and compete to create a sometimes bewildering if not cacophonous work environment.

Confusing and noisy - yes. Wasteful? Probably not. Quite the contrary, in fact.

In knowledge work, value is created through often unplanned human interaction. Water cooler conversations, instant message exchanges, seemingly interminable and ostensibly “useless” meetings, and serendipity combine to create customer value. Indeed, oftentimes customers themselves end up contributing to this continuous conversation.

Office workers usually have multiple projects with their own constituencies, deliverables, and anomalies. This creates a “noisy” interdependent environment with a very different relationship to variation than the one that exists on the shop floor. When it comes to knowledge work, variation - change - is a constant. No two financial audits will occur the same way. No two court cases will require the same strategy.No two treatment plans will offer the same course of action.

Oftentimes this change is how an organization learns. In the office, learning is the driver of successful projects, myriad improvements, and satisfied stakeholders.

Because of this, knowledge workers’ value streams have a very short shelf life. This does not mean they have no value stream, nor does it mean that their value streams are an effort in futility. Rather, their value streams ebb and flow with the work itself. They will stabilize and allow for the creation of a project-specific value-stream, but one which will always require continuous adjustment and improvement.

Therefore in knowledge work, flow comes not through relentless standardization and waste reduction, but through the continuous optimization of processes with a very short shelf-life. When it comes to optimizing flow in the office, the value stream is in a perpetual state of kaizen (which will be discussed in the next section).

How to mitigate:

In the office, flow is interrupted not by communication per se, but by unnecessary communication or the interruption of focus. For a person or a team, their focus is maintained when they have a single task that they are allowed to complete unimpeded.

The issue in the office is that countless tasks are being processed simultaneously and whether they are self-imposed or external, interruptions are both frequent and inevitable. This is necessary for the organization’s learning, but it does not have to arrive chaotically. They can be batched to process similar tasks together. They can be analyzed to see where they emanate from and why. They can be scheduled. They can be be processed more thoughtfully.

Visualizing work as a team, as well as interruptions, allows team members to see when an interruption is least disruptive. Limiting WIP lowers the amount of potential interruptions (less people asking for status or seeking additional information). And techniques like working meetings and Pomodoros allow staff to sequester themselves for short periods of focus.

The overall goal to achieve flow in the office rests in creating pockets of focus to allow work to achieve completion. We do not, however, want to over-regulate work or stifle conversation because, while it is often unplanned, this type of variation is where true learning occurs.

Up next in The Lean Brain series: Push is Blind. Pull is Informed. See Beyond the Silo.

Earlier posts in this series:

Introduction: 5 Ways Our Brain Can Thwart Lean

Post 1: Value is a Conversation

Post 2: Visualization Begets Alignment

Tonianne is partner & principal consultant at Modus Cooperandi, co-author of the Shingo Research and Publication Award winning Personal Kanban: Mapping Work | Navigating Life, co-founder of Kaizen Camp™ and Modus Institute. Toni explores the relationship between performance, motivation, and neuroscience, is passionate about the roles intention, collaboration, value-creation, and happiness play in “the future of work,” and appreciative of the ways in which psychology, Lean, systems thinking, and the work of W. Edwards Deming can facilitate these ends. She enjoys Coltrane, shoots Nikon, butchers the Italian language (much to the embarrassment of her family), is a single malt enthusiast, and is head over heels in love with her adopted home, Seattle. Follow her on Twitter @Sprezzatura.

The Lean Brain, Post 2: Visualization Begets Alignment

Lean says: Map the Value Stream Your brain says: I’ve been doing this so long, it’s become second nature to me. The steps are right here - in my head.

What’s at play here: Illusion of Transparency. Curse of Knowledge/Information Imbalance. Status Quo Thinking. Groupthink/False Consensus Effect. Availability Bias.

It was day four of the value stream mapping exercise and tempers were beginning to fray. Despite having worked together for years, the members of this outwardly cohesive development team struggled to identify the basic activities needed to create value for their customer. While at 17 steps they agreed they were close to completing a first pass of their map, they couldn’t seem to reach consensus when it came to certain conditions and boundaries and for some, even the target was nebulous.

If they couldn’t agree on how they currently operate - without that clear baseline - how could they improve their future state?

Oftentimes the curse of expertise is the assumption that other people’s interpretation of events matches our own. So long as the value stream is left implicit, the steps - the order, the handoffs, the standards - are highly subjective. As a result, effort is duplicated. Unnecessary churn occurs. Bottlenecks and work starvation become business as usual.

And no one seems notice.

How to mitigate:

Especially when it comes to non-routine creative work, eliminate assumptions and normalize expectations by making the current state explicit. Visualizing steps essential to the process exposes mismatches, surfaces non-value-added steps (waste), and promotes constancy of purpose.

Up next in The Lean Brain: Flow: You Can’t Step in the Same River Twice

Earlier posts in this series:

Introduction: 5 Ways Our Brain Can Thwart Lean

Post 1: Value is a Conversation

Tonianne is partner & principal consultant at Modus Cooperandi, co-author of the Shingo Research and Publication Award winning Personal Kanban: Mapping Work | Navigating Life, co-founder of Kaizen Camp™ and Modus Institute. Toni explores the relationship between performance, motivation, and neuroscience, is passionate about the roles intention, collaboration, value-creation, and happiness play in “the future of work,” and appreciative of the ways in which psychology, Lean, systems thinking, and the work of W. Edwards Deming can facilitate these ends. She enjoys Coltrane, shoots Nikon, butchers the Italian language (much to the embarrassment of her family), is a single malt enthusiast, and is head over heels in love with her adopted home, Seattle. Follow her on Twitter @Sprezzatura.

The Lean Brain, Post 4: Push is Blind. Pull is Informed. See Beyond the Silo

Lean says: Establish Pull Your brain says: I work best under stress! Chaos motivates me!

What’s at play here: Brain on Stress. Learned Helplessness.

Most of us have seen the iconic “Job Switching” episode of I Love Lucy, where the titular character and her BFF Ethel find themselves doing a stint as line workers at Kramer’s Candy Kitchen. Subjected to organizational silos and a despotic supervisor who rules with a capricious conveyor belt and leads with the threat of expulsion, the women’s only KPI is to ensure not a single piece of candy makes it into the packing room unwrapped. Aligning their performance to this solitary target, they resort to hiding unwrapped chocolates in their mouths, their blouses and most memorably, in Lucy’s oversized chef’s hat.

Their excessive WIP and struggle to keep apace at 100% utilization, coupled with a toxic KPI which makes zero mention of producing a quality product, creates a system that forces an overwhelmed Lucy and Ethel to produce defects and hide wasted inventory necessitating rework, causing stress and chaos, and ultimately resulting in burnout (not to mention their respective stomach aches and ultimate dismissals from the company).

At this candy factory, supply rather than demand drives process. Work is being pushed onto Lucy and Ethel when they have neither the capacity to process it nor a signaling mechanism to slow it down or make it stop when a moment to breathe is needed. Upstream workers in the kitchen have no insight into the capacity of downstream workers in the wrapping room and in turn, workers downstream in the packing room are no doubt starved for work as they are left waiting for product.

Devoid of any context beyond their own work station, the hapless line workers - through no fault of their own - are oblivious to the fact that the wrapping room is part of a larger system. As a result, they are incapable of seeing the impact of their work-as-a-bottleneck on other parts of the value stream.

When we become overloaded, we focus myopically on our tasks rather than on their flow. Constantly forced to react we fail to be thoughtful about what it is we are doing, conceding control over our situation. Confronted with our own lack of agency we default to relying on others to push work on us, rather than pull it ourselves. Once this learned helplessness takes over, flow breaks down, and any hope for kaizen becomes futile.

How to mitigate:

This classic TV clip masterfully breaks almost every tenet of Lean thinking. Lucy and Ethel lack clarity over their roles, their goals, and the value stream; they have no visualization mechanism to understand their own capacity or a communication mechanism to convey it to others; they are assigned to a supervisor who rates rather than develops their performance; they’re driven by fear in the form of a useless KPI; they are afforded zero respect (agency) to stop the process when problems arise nor do they have the slack or support to so much as suggest improving their process.

Pull requires us to build thoughtful systems that allow for upstream and downstream transparency, continuous feedback, respect-as-agency, and easy adjustment to ensure changes and improvements are made in context.

Pull provides pockets of predictability and pause, allowing downstream workers to plan for, focus on, and complete work with quality while having enough slack to pursue kaizen opportunities.

Whereas pull in manufacturing seeks to prevent overproduction, so too does pull in a knowledge work setting.

What is overproduction in knowledge work? Burnout.

While extreme stress might serve as a positive motivator for physical performance and as such, prove beneficial to athletes, studies show it has the opposite effect on knowledge workers, impacting cognitive capacity - actually contributing to WIP - compromising overall performance and quality.

Whether actual or perceived, physical or cognitive, extreme stress activates the brain’s threat circuitry, shutting down all non-essential functions so as to direct the body’s attention towards eradicating the potential danger. Among those functions considered “non-essential” are digestion, the immune system, and most important to knowledge workers, higher level thinking. When we are stressed, the neurotransmitter dopamine floods the prefrontal cortex - the part of the brain responsible for executive functions - which includes our ability to concentrate, plan, organize, memorize, learn, problem-solve - the very skills essential to knowledge workers.

Utilizing a light-weight, flexible visual control like a Personal Kanban provides knowledge workers with a framework for understanding personal and team workloads and workflow. It gives them transparency into both the upstream supplier and the downstream customer’s context, as well as the opportunity to recognize and communicate to others their capacity to take on or defer more work. The associated WIP limit prevents them from taking on more work than they can handle, limiting cognitive stress thus allowing them to focus on and finish with quality only those tasks they have the mental capacity to process.

Up next in The Lean Brain: Post 5: Improvement is Not an Option

Earlier posts:

Introduction: 5 Ways Our Brain Can Thwart Lean

Post 1: Value is a Conversation

Post 2: Visualization Begets Alignment

Post 3: Flow: You Can’t Step in the Same River Twice

Tonianne is partner & principal consultant at Modus Cooperandi, co-author of the Shingo Research and Publication Award winning Personal Kanban: Mapping Work | Navigating Life, co-founder of Kaizen Camp™ and Modus Institute. Toni explores the relationship between performance, motivation, and neuroscience, is passionate about the roles intention, collaboration, value-creation, and happiness play in “the future of work,” and appreciative of the ways in which psychology, Lean, systems thinking, and the work of W. Edwards Deming can facilitate these ends. She enjoys Coltrane, shoots Nikon, butchers the Italian language (much to the embarrassment of her family), is a single malt enthusiast, and is head over heels in love with her adopted home, Seattle. Follow her on Twitter @Sprezzatura.

The Lean Brain, Post 1: Value is a Conversation

Lean says: Define Customer Value

Your brain says: I’ve seen this countless times before - I know what my customer needs better than they do.

What’s at play here: Expertise bias. Overconfidence effect. Ivory tower syndrome. Ego.

There’s an old story about a man standing along a riverbank. He doesn’t see a bridge, but he does see someone on the opposite bank fishing.

“Hey!” he shouts across the water. “How do I get to the other side of the river?”

The other man yells back, “You’re already on the other side of the river!”

Perspective. More than our own exists. Unfortunately we’re not wired to immediately see things beyond our own context and so from an anthropological standpoint, having a self-centered worldview makes perfect sense. Man’s survival did not depend on knowing what his fellow hunter-gatherers thought, felt, or needed. Biologically speaking, seeing things from our own side of the proverbial river is cognitively expedient - it’s quick, convenient, and let’s face it practical.

Acknowledging there might be an alternative or even multiple perspectives, acknowledging “their there” might deviate from our own requires mental effort. When we fall into the trap of assuming only one truth, of applying a singular mental model, we miss inherent complexities and nuances obliterating not only the possibility of finding better alternatives, but we guarantee that we will at some point fall short of our customer’s expectations.

How to mitigate: Your gut instinct, you experience, your myriad belts and certifications and mastery aside, you do not know what your customer wants. And THEY are the arbiter of value, not you. Replace assumptions with humility. Ask open-ended questions. Endeavor to gain an unbiased understanding of - and deeper insight into - what your client explicitly wants and why.

Next up in The Lean Brain series: Visualization Begets Alignment

Tonianne is partner & principal consultant at Modus Cooperandi, co-author of the Shingo Research and Publication Award winning Personal Kanban: Mapping Work | Navigating Life, co-founder of Kaizen Camp™ and Modus Institute. Toni explores the relationship between performance, motivation, and neuroscience, is passionate about the roles intention, collaboration, value-creation, and happiness play in “the future of work,” and appreciative of the ways in which psychology, Lean, systems thinking, and the work of W. Edwards Deming can facilitate these ends. She enjoys Coltrane, shoots Nikon, butchers the Italian language (much to the embarrassment of her family), is a single malt enthusiast, and is head over heels in love with her adopted home, Seattle. Follow her on Twitter @Sprezzatura.

Introducing The Lean Brain Series by Tonianne DeMaria

“All problem solvers must…”

Given how the work we do at Modus Cooperandi focuses largely on the nexus between Lean for knowledge work, behavioral economics, neuroscience, and the teachings of W. Edwards Deming, one response in particular resonated:

“Understand how their behaviors are contributing to the problem.”

While Lean offers us a set of principles and practices to help us create value for our customers, for our organizations, and for ourselves, it’s our brains that seem to pose the greatest challenge to its successful implementation.

But it’s not our fault, you see. Our brains hate us.

Okay, so maybe that’s a bit harsh. They do nevertheless tend to act in their own self-interest to conserve cognitive energy - opting for rapidity over reason - often sabotaging our best intentions with their behavior-impacting shortcuts. Which is precisely what Jim Benson and I have encountered in the hundreds of workshops we’ve offered where we ask participants, What is your biggest impediment to implementing Lean?

The universal response? Myself.

To understand why this is, we need to look no further than the System of Profound Knowledge (SoPK). With SoPK, Dr. Deming explains how people and processes are all part of a complex web of interrelated systems. Among those is our cognitive system.

In contrast to that which is found on the factory floor, knowledge worker’s “machinery” - their brains - can be capricious, rendering thought processes less than reliable, and actions less than rational.

For Lean thinkers who engage in knowledge work, even a cursory understanding of how the brain can contribute to behaviors impeding Lean’s five key principles (as Dr. Deming instructs, having an understanding of psychology) is crucial to identifying where Lean efforts might become sabotaged.

So stayed tuned for my latest series of posts: The Lean Brain.

Post 1: Value is a Conversation

Post 2: Visualization Begets Alignment

Post 3: Flow: You Can’t Step In the Same River Twice

Post 4: Push is Blind. Pull is Informed. See Beyond the Silo

Post 5: Improvement is Not an Option

Fresh Perspectives on Lean Coffee

The following is a guest post by Victor Bonacci. Question #1: Do you like coffee?

I do. I enjoy it warm or on ice. I love the smell. I get excited with the neurochemical reactions it stirs in me. I find calmness in the process of brewing a cup. It’s a fun word to say: “coffee.”

Coffee is a casual sport. Grabbing a coffee with a friend or colleague is often an impromptu act. Someone is more likely to agree to meet for coffee than to accept my invitation to dinner.

With coffee, the investment is low. Topics are light and change rapidly. The environments where we drink our coffee often vary in eclectic and inviting ways.

Question #2: Do you like meetings?

I’m going out on a limb to guess that you may not hold the meetings in high esteem. A typical work meeting runs too long, is unexciting (if not downright boring) and usually less effective than it can be. The conversation may be more monologue with one person dominating - usually the one who arranged the meeting. The meeting’s agenda is pre-planned with perhaps no collaboration or input.

I don’t know about you, but I see the score as “coffee: 1, meetings: 0.”

Whose Reality Is It Anyway?

This is why I love Lean Coffee. It replaces the tyranny of the meeting with something that is effective, engaging and (dare I say) fun. (We can’t say that in the office, though, where “Fun” is a four-letter word.)

Lean Coffee meetings (I often refer to these simply as “coffees”) are, in the Agile parlance, self-organizing. They get us involved. The coffees stimulate our natural curiosities and keep us from answering multiple choice questions with a “true/false” answer.

You’ve heard the parable of the blind men describing the elephant. We each have our own perspective - our own “reality tunnel” as Tim Leary was fond of saying. At a coffee, topics get considered and described by any number of perspectives, each voice providing a slight turn to reveal different facets. It’s the “wisdom of crowds” rule: the more voices contributing the the conversation, the closer to the “truth” we can arrive.

I’ve used lean coffees in a multitude of settings, and I’d like to highlight two. If you’re already familiar with the mechanics, it’s easy to imagine meet-ups or retrospectives using this lightweight format, so I’ll skip those in favor of some less obvious applications.

One for the Roadmapping

First let’s consider the workplace. I’ve alluded to using coffees in retrospectives, but what if you’re not a Scrum / Agile shop? There may still be a number of meetings that can follow the Lean Coffee format. One that I’ve had success with recently is tied to the Roadmapping process, a staple of the yearly business cycle. I work with technology folks who, independent of the sales pipeline, are asked to list, size and prioritize some set of initiatives that are either wanted (eg. trying out a new language) or needed (eg. addressing tech debt) by the engineering departments.

When I try to recruit participants (usually a subset of architects, team leads, etc.) for a roadmap planning session, everyone spontaneously seizes up and/or runs from the room. If on the other hand I invite them to a planning coffee, curiosity may outweigh feelings of obligation. When the dozen-or-so victims, er, members arrive, they see an inviting table with index cards, markers and coffee carafes (optional). We chit chat until enough people are there to begin, not always waiting for or worrying about the stragglers. A quick explanation of the coffee rules, and we’re off writing our wishlist items onto 3x5 cards. People are out of their chairs, their brains getting more oxygen then at standard (death-by-)meetings, and the mood stays light. Cursing about this or that “problem” with our current development environment often elicits chuckles from across the table.

Affinity mapping the cards is a fantastic cue for glimpsing the importance of a topic, but we still do some dot-voting after each topic card (or group of cards) is summarized. If we ended the meeting at this point, we’ve already collected more information transparently and asynchronously in under ten minutes than we could have hoped for in a two-hour session going around the table with each representative speaking up in turn. Still, we play out the hour-long event asking questions of and examining the top few topics.

For roadmapping, I’ll take these data (topics cards, votes, added explanations) and compile it onto some shared document. Others throughout engineering are free to read this and add or update as they like. I’ve been successful using other methods (such as DeBono’s Six Thinking Hats) to add more dimension to the list before turning it over to engineering leadership. The CTO appreciates that the entire exercise not only spanned days (not weeks), but also remarks how pleased she is that the department “owns” (has defined and is accountable for) the list. It makes her job of negotiating with other management much easier.

Cast a Wide Coffee

Another application that caught me by surprise came as an offshoot of our community meetups. Like most of our caffeine-fueled sessions, the topics were interesting and the discussions lively at the coffeehouse in February, 2014, and I didn’t want the conversation to simply fade into the ether. So I put the topic out there: recording the coffees to make a podcast. Heads nodded as encouragement and suggestions flowed. So I bought some basic recording equipment (mics, cables, a small mixer) and invited a small number of regulars to a special event.

We arrived to record a show with only a modicum of nervousness. (For my part, I was mostly occupied with the technical aspects of recording.) As soon as we began the actual coffee, however, nerves were forgotten as the conversation took over. There was no script, no set of pre-determined questions to cover. Only the cards.

The Agile Coffee podcast is now twenty episodes into its life, with no sign of slowing down. And although we’ve got a few hundred downloads each week, I find incredible value in simply re-playing the conversations that I’ve already participated in. I hear more, nuances that I missed in earlier listens or applications that make sense to my present self and situation.

We are experimenting with twitter and other media to enlarge the conversation, driving voices to our forums to continue the dialog after the timebox has expired. So far we’ve only recorded the voices of participants physically at the same table, but we’ve got plans to use Skype or other means to bring enough fidelity to have a rich coffee with people geographically dispersed.

Last Call

One final tip I’d give is: no matter how you use Lean Coffee, holding an occasional retrospective on your process will help make future coffees more effective. You may decide to extend or shorten the timebox, for example; or decide to accept new cards (and re-vote) mid-coffee. Changes that allow the group to make the Lean Coffee experience more meaningful should be the goal. You may also come up with alternative applications for coffees during the retrospective, ideas that may otherwise not surface.

And when these alternative uses surface, take a chance and try Lean Coffee. Let others know how you’ve used it, and share your results. Do your part to kill tyranny of the bloated meeting, replacing it with a fine brew of Lean Coffee.

Victor Bonacci (@AgileCoffee) is a coach and community organizer in Southern California. He produces the Agile Coffee podcast and blogs at agilecoffee.com. Vic will be the facilitator of the Agile Coach Camp in Irvine, CA, from April 10-12, 2015.

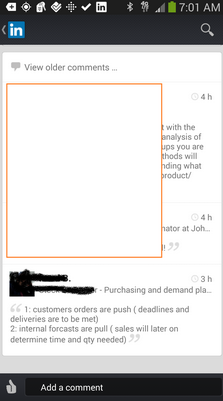

Fundamental Misunderstandings Lead Directly to Malpractice

Yes, I know I know, Somebody’s Wrong on the Internet!  I am somewhat ranting this morning, because the screenshot to the right is so disappointing. The redacted person is responsible for implementing Lean in his organization, but I see this with all types of systems.

I am somewhat ranting this morning, because the screenshot to the right is so disappointing. The redacted person is responsible for implementing Lean in his organization, but I see this with all types of systems.

The redacted person, let’s call him Micro, has a fundamental misunderstanding of the guiding principles of how he works. In this case, he believes that customer orders are a push system. Meaning he believes customer orders force work on his production system, rather than events to engage his production system.

For the general public, this is a fairly esoteric concept. But for Lean it’s about as important as an electrician claiming that live wires were okay to grab with your bare hands.

(Trust me, it’s so tempting to go into a lecture on pull systems right now…)

But I’m running into this more and more lately, people who are active in their communities misunderstanding fundamentals of their espoused beliefs. This guy is active enough to participate in open forums, speaking knowledgeably about Lean and answering questions for people just starting out.

Whether you are employing elements of Lean, “Agile”, Six Sigma or any other flavor of standardized process control - you need to grasp the basics first.

In December, I wrote this blog post on making sorbet. In this post, I show that there are fundamental things (a core) to making sorbet. On top of that core you have a lot of leeway to innovate. There is a platform for sorbet that provides it with the minimal structure to be sorbet.

You cannot make sorbet without water. You cannot make sorbet without some sort of sugar. You cannot make sorbet without it becoming cold.

You can make sorbet with just about anything else on earth.

We need to understand the core of our work. We need minimal structure to build upon. Without that structure, we cannot communicate, we cannot plan, we cannot have coherent systems.

In this case, this guy is going to build systems claiming to be Lean that are completely contrary to everything Lean is trying to do.

Please, people who consider themselves coaches, senseis, leaders, managers … learn the systems you are employing and then innovate.

The Client Management A3: Modus Cooperandi White Paper #2

Lean thinkers seek systemic causes to workplace or project issues. The goal is to find procedural or functional root causes to unpopular behaviors or outcomes. Psychologists warn us of Fundamental Attribution Error, a common human bias that leads us to blame before we analyze.

Lean thinkers seek systemic causes to workplace or project issues. The goal is to find procedural or functional root causes to unpopular behaviors or outcomes. Psychologists warn us of Fundamental Attribution Error, a common human bias that leads us to blame before we analyze.

Lean uses the A3 as a tool to examine problems, hypothesize solutions, and then run experiments to test those hypotheses.

But sometimes, people might actually be the system we want to fix.

In software development, there is the notion of the Persona - which helps software developers build empathy and understanding for those unlucky enough to use their software. At a recent client engagement, we combined Personas with an A3 to some interesting results.

This paper is the result of that endeavor.

The Client Management A3 White Paper is available from Amazon.